There’s a lot of hate going round for Daisy Buchanan at the moment. As one particular example, a friend’s English teacher apparently told the class that Daisy had – and I quote – ‘no soul.’ Critics have described her as ‘frivolous’; ‘an empty vessel’; ‘an emptiness that we see curdling into the viciousness of a monstrous moral indifference as the story unfolds’ - a sentence so dripping in vitriol that to read it is to feel poisoned.

She’s ‘superficial’ and ‘a tease’ on Thought Catalog – ‘someone who doesn’t take responsibility for [her] legacy’, the legacy being that which Gatsby has built up around her like a huge inescapable prison with electric wires. Which is something she should totally have to take responsibility for.

Daisy has been getting flak for years and it’s incredibly unfair. Readers are forgiving towards other flawed and vulnerable women in literature – off the top of my head, they have certainly warmed to both Tess Durbeyfield and Anna Karenina (who, it’s fair to say, both make epically bad decisions.) Yet there’s a special kind of vitriol reserved for Daisy.

Is this because Daisy, unlike Tess and Anna, lives? Readers claim to be heartbroken at Tess’ fate and the awful fates of other literary heroines, but is there a bloodthirsty part of us which calls for the death of these ‘fallen women’? Does Daisy need to die before we can forgive her, so then we can be all weepy and sad and entomb her in the false dream where she ‘belongs’?

Below are some of the reasons commonly cited for hating Daisy Buchanan, where I explain why these are basically shitty reasons to hate anybody.

1) Daisy married Tom rather than waiting for Gatsby – she must be a shallow floozy

In Jordan’s account of Daisy’s youth, she shows us an extremely vulnerable young girl who is also a dreamer, a romantic – a girl who has learnt to expect the world to love and protect her and therefore has an acute and touching naivety. Gatsby and Daisy’s love story blossoms from this innocence. Jordan remembers seeing them as young lovers - “The officer looked at Daisy while she was speaking, in a way that every young girl wants to be looked at some time.”

After he has gone Daisy tries to follow him against her family’s wishes, yet is eventually stopped: “Wild rumours were circulating about her – how her Mother had found her packing her bag one winter night to go to New York and say goodbye to a soldier who was going overseas. She was eventually prevented, but she wasn’t on speaking terms with her family for several weeks.”

Surely the above quote demonstrates how conflicted Daisy was, how torn between the wishes of her family that she should marry a wealthy man, and her wish to marry Gatsby. Even at this point she makes a bold stand against her fate, agreeing to wait for Gatsby til he leaves the army – however he then, inexplicably, disappears to Oxford, leaving Daisy surrounded by other more mum-and-dad friendly suitors. To go against her family’s wishes would have been almost incomprehensible for a girl as sheltered as Daisy, though it’s clear even on the night before her wedding that she hasn’t forgotten Gatsby, when she lies on her bed drunk and saying “Tell ‘em all Daisy’s change’ her mine. Say ‘Daisy’s change’ her mine!”

It’s also worth bearing in mind that she does love Tom, at least at first before his infidelities become apparent.

2) Daisy doesn’t talk about her daughter all the time – she is obviously a terrible mother

One of the first things people know about Daisy is that she wants her daughter to be “a beautiful little fool.” Yet this quote is often taken out of context. When Daisy says this she is lying in hospital, feeling entirely abandoned, with no idea about the whereabouts of her own husband. The life of promise she lived before has eluded her, and she has been left all alone with a young baby that depends on her.

Her desire for her child to be beautiful is natural; in Daisy’s world, beauty equals love. As a girl who was in many ways powerless to choose her own path, beauty was, tragically, Daisy’s only strength. This does not demonstrate that she is vacuous, frivolous and silly, but rather that she values the one aspect which she believes can give women power. Yes, it’s appalling that she felt that way – but that says more about her society than her character.

Wanting her daughter to be a ‘fool’ is more problematic; however, Daisy came from a set where women were not valued for their intelligence, and she has seen firsthand how hurtful it can be to know too much of human nature. Ignorance and beauty may not be virtues, but they are the two things which Daisy believes will best equip her child to cope with the world.

Although these waters are difficult to tread, it’s also perfectly possible that Daisy may be in the midst of unrecognised postnatal depression. This would certainly explain her seeming disinterest in the child when Nick first asks about her – “I suppose she talks and eats and everything.” Her strange detachment, as well as her bitterness towards the world in which the baby is born, may well indicate this.

It should also be taken into consideration that Nick Carraway is a fallible narrator. Daisy might spend more time with the child when there are no visitors, and the little girl may also play a vital part in Daisy’s decision to stay with Tom. This is never stated – however, when Tom and Daisy are seen through the window talking earnestly, Carraway does not know what’s being said.

Gatsby asks Daisy to wipe out the last five years, but the little girl is a part of that. Daisy, while wishing to wipe out Tom and his infidelities, can never wish the child did not exit.

As for Gatsby – “He kept looking at the child with surprise. I don’t think he had really believed in its existence before.” ‘Nuff said.

3) Daisy kills Myrtle then lets Gatsby take all the blame – what a bitch

This is the most problematic aspect of Daisy by far, and one which is, to use an understatement, definitely not cool. It’s true that Myrtle does run out at the car to try to stop it, that Daisy is nervous and upset, that she’s an awful driver – but none of these are excuses. All we know is that the killing of Myrtle was not a deliberate act, but a sickening awful coincidence (perhaps one brought about by the all seeing eyes of Dr T J Eckleburg.) Daisy certainly had no idea that Myrtle was Tom’s mistress.

Daisy’s reactions demonstrate her remorse: she falls weeping on Gatsby’s lap while he takes control of the car. She is profoundly shocked, scared, sorry.

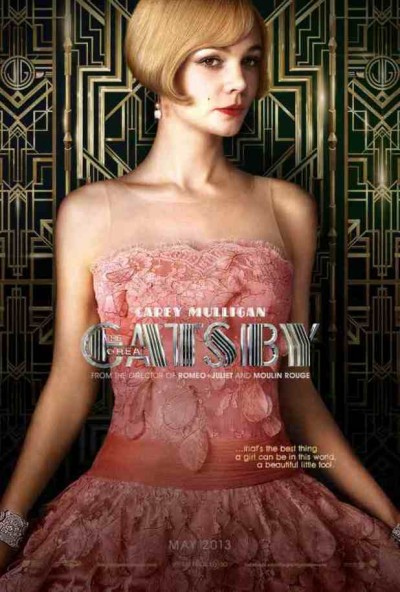

Gatsby offers to say he was driving and she allows him to. This is cowardly and almost unjustifiable, but could she have accepted out of fear? And does it make it any better if she did? Her grip on reality is slippery at best; as Mulligan said of Daisy in her American Vogue interview – “She’s constantly on show, performing all the time. Nothing bad can happen in a dream. You can’t die in a dream.”

And let’s remember at this point that we forgive Tess for murder, even if the world does not.

4) Daisy fails to live up to Gatsby’s dream

Almost every girl has at one time or another been put on a pedestal – and it’s a terrifying place to be. Pedestals set you up for failure like nothing else, and the pedestal Gatsby has built for Daisy is, well, The Biggest Pedestal Of All Time. Falling from that height, a girl is going to get hurt, even “the king’s daughter, the golden girl.”

When Gatsby and Daisy are triumphantly reunited, reality comes along as a qualifier – “There must have been moments even that afternoon when Daisy tumbled short of his dreams – not through her own fault but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion.” Gatsby, even whilst basking in Daisy’s presence, is saddened that the green light at the end of her harbour has ceased to have significance. For him, she has become so idealised that she has ceased to be real; for Daisy, her idealised view on the world has also fatally divorced her from reality.

Daisy may fail to live up to the dream, but she only ever pursued a future in which she could be happy, secure and loved. She certainly never constructed the dream herself.

5) But…she cries when she sees his shirts! She cries because of pretty shirts!

Shut up, she doesn’t cry because of pretty shirts. She cries because she is so overwhelmed by being reunited with Gatsby and seeing all he has built for her. The shirts are a symbol for this.

And FYI, I can totally see how, given the right circumstances, a girl could cry over shirts.

Hmm…I don’t buy the ‘Daisy is victimised’ angle. Nick Carraway is a slippery narrator at best but this quote sums it up for me: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy- they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.” Fitzgerald is just as scathing about Tom throughout the book: it’s their ‘old money’ social strata, and the behaviours Fitzgerald assigns to it, that is under attack. Daisy is unsympathetic because she’s careless. Tess is (to me, anyway) a hundred times more sympathetic because she’s a woman more sinned against than sinning – and she is repeatedly, horribly punished for her alleged ‘mistakes’. Daisy isn’t. She is protected by her money – I think that’s what’s under attack in Gatsby.

I think it’s OK to dislike Daisy – she’s not written as a particularly sympathetic character whereas Tess is the heroine of Hardy’s novel – but a lot of the time people single her out, or give odd reasons for disliking her (like that she fails to live up to Gatsby’s dream – on another note, anyone who sees the flaw here in Daisy and not the dream is drastically missing the point, in my opinion…) Anyway, I got a bit sidetracked but my point was that it is OK to dislike Daisy because she is kind of terrible, but that a lot of people get kind of sexist about it, because let’s face it, everyone in that book is as awful as each other (and I say that as a fan).

The character of Margarita in Bulgakov’s “Margarita and the Master” is a rich woman encased/trapped in a golden cage of money, marriage and respectability, who we might think is having 1st world problems when deciding to kill herself the day she falls in love for another man…. she repeatedly betrays and later leaves her husband, who she describes herself as beyond reproach…and yet, I never felt for the character the distaste I have for Daisy….

Daisy focused herself on wealth and respectability in order to survive a broken heart… for long I thought she was stupid because she could have had it all, but nowadays I think she was a totally different person than the one Gatsy fell in love with, once able to be with him again, she does it for caprice…if anything, going with the flow passively….

I keep thinking that if Gatsby had lived and somehow it had been Daisy’s husband to die, she wouldn’t have skipped a beat the same way she didn’t in the novel regarding Gatsby’s death…

Margarita is willing to die the moment we meet her….dismisses completely notions of wealth and respectability and even attempts to sell her soul when invited by the Devil to be his queen of the ball…..

I think it’s the strength of character or lack of it that make the difference in my appraisal of them both… ……Ok, and a fair bit of romanticism….

Daisy just isn’t a good character. She doesn’t need to be defended because quite frankly none of the characters are likeable or ‘good’ in Gatsby inany case. That’s kind of the point of the novel. We’re not supposed to sympathise with them, we’re supposed to recognise that behind the beautiful veneer the people are very ugly.

In my experience, Daisy doesn’t get more hate than Tom or Gatsby. In fact more girls actually idealise her like Gatsby does because she’s pretty and tragedy circles her, and it’s all very glamourous. That’s more infuriating.

Granted she has an absolutely monstrous husband, and in that sense I can sympathise with her wanting to escape into her past with Gatsby again. It’s understandable and somewhat justified. But Gatsby himself treats her like some sort of doll, which is also rather appalling. She’s a product of her environment, and her environment has made her into a childish and selfish person. That’s part of the tragedy.

Quite frankly, you can’t excuse her actions towards the end of the book. She straight up kills somebody and, even if it was accidental, crying over it does not a victim make. She is completely incapable of facing up to reality or the consequences of her actions. You’re not supposed to try and justify what she did, it’s the reason Nick finally cuts ties with the Buchanans.

Hating Daisy Buchanan isn’t a feminist issue, it’s a character issue, and her character isn’t likeable in a lot of respects. She’s also not deplorable. Just like a lot of the characters in Gatsby, she’s multi-faceted, and that’s one of the great things about the novel – and the film, I guess. Most importantly, you can’t make comments on someone’s character through speculation on what MIGHT have not been seen in the novel or reported by the narrator. If that was the case you could say that maybe Nick was actually making the whole thing up. And of course Daisy doesn’t live up to Gatsby’s dream, that’s the whole point of the novel in a lot of respects – she’s become a memory to him and fails to be the person he remembers her as. That’s not a criticism of Daisy’s character, it’s a part of the plot…

It’s probably more fair to let students come to their own assumptions… which I do and, all my students hate Daisy a lot more than I did when I read the book!

The greatest moral mistake Daisy makes is not even running Myrtle down and leaving her to die in the dirt. It’s not going to Gatsby’s funeral, or showing any kind of remorse for what she’s done. She is as Nick says ‘a careless person’ who smashes things up. Gatsby, who you make a strong argument for Daisy once loving, is murdered through her carelessness. After this is there a flower or a note sent in recognition of his sacrifice for her? Of course not. I completely agree with

BollardsUpAhead22 May 2013 16:34

Hating Daisy Buchanan isn’t a feminist issue, it’s a character issue.

But maybe it’d be more convincing to make a general argument about Fitzgerald having an antifeminist stance- Myrtle is portrayed as deeply unattractive, morally and physically and dies for luring a married man away. Jordan a golf cheat, who is unceremoniously dumped. Other women in the novel who also just seem to be out for what they can get, I’m thinking of the girl who ripped her dress at Gatsby’s party.

Perhaps it’s not Daisy, but women in general who we should be examining?

I don’t think Fitzgerald had any sort of anti-feminist stance in the novel.

As pointed out in other comments, other characters have flaws too. I’d go as far as to say all of them.

The story isn’t told in terms of men and women… it’s told in terms of public appearances, public virtues and private vices…

it’s told in terms of Gatsby and The Rest.

We’re presented with an idyllic little setting, of simple folk leading a simple life, rich or poor, all carrying along and getting along fine and dandy in their simple virtuous life…. then enters Gatsby, who left poor and returned rich and mundane, shrouded in mystery with a whiff of crime, illegality, something reproachable…

As the story progresses as our knowledge of Gatsby and the rest deepens, the tables turn as the rest of the town are shown to us as liars, cheaters, egotists, murderers and generally shallow, Gatsby also turns around and reveals himself to be in end the only truly innocent character of the whole story.

It’s about public virtues, private vices and societal facades, how people sometimes turn out to be the complete opposite of what we’re expecting them to be, or the way we are told we should expect them to be…both for the negative and for the positive…

That’s what the story’s all about for me…

On the final point, it’s worth remembering the rather significant shirt in Brokeback Mountain, which becomes the focus of a prolonged, melodramatic and morbid attachment. It ain’t only ladies who tear up over a nice bit of tailoring now and then.

i think this defense would be a great one, and one I’d agree with, if it was about a real woman. But you can’t forget that Daisy is fundamentally the creation of Fitzgerald who was interested in portraying the absolute emptiness, materialism and vacuity of his society, who described Daisy as having a voice that is ‘full of money’, that ‘jingles’ like change and who had a pretty vexed relationship with women (and modeled Daisy partly on Zelda)

I love Daisy because she’s awesome. Just kidding, I haven’t seen the Great Gatsby yet but I will soon. But really, I already love Daisy because she’s played by Blink girl! (the Sally Sparrow in Doctor Who)

Daisy was just a bitch. No matter how far you try to convince yourself or others that she was nice, situation made her change. It’s all money. Her mouth is full of money.

This could be alluded to reality. That was why this novel is known to be the greatest novel of 20th century.