We all need to talk about Jane.

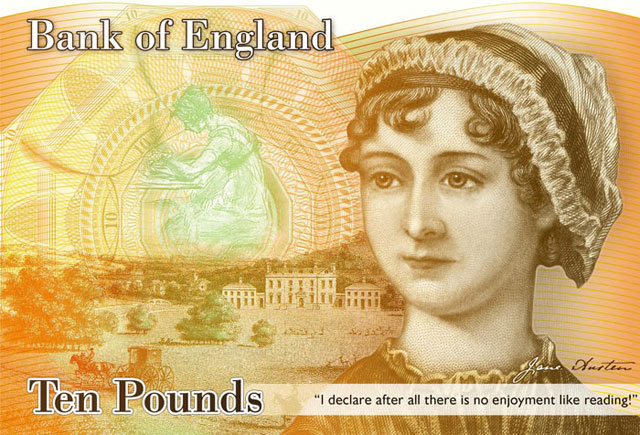

She’s going to be appearing on the ten-pound note, replacing Darwin, from 2017. Sweet, inoffensive Jane Austen, provider of solace for women everywhere, producer of Mr Darcy and by proxy that wet shirt, and steady source of income for the BBC in the form of about a million period dramas.

And yet, my Twitter feed has been filled with people, feminists and otherwise, moaning about this inoffensive, bland, mother of chick-lit, not-really-revolutionary author. ‘Of course they chose her,’ they say, ‘There’s nothing controversial about her.’ I moved on to the comment boards on news sites, which are, incidentally, all saying the same things. Some newspapers repeated this idea, giving examples of women who were more ‘revolutionary,’ and therefore appropriate, like Mary Wollstonecraft, Boudicca and Rosalind Franklin.

Well, all of those women should have a shot at being on our money, and it’s unfair that the Bank of England maintains their tokenism in having one woman on its notes and three men, when over half of the population of England, and the world, is female. (And to all of those people who think they’re exceptionally clever in pointing out the Queen is a woman, and is on all of our money, they really should learn about how all the money now shows the monarch, regardless of gender, and ….. oh my GOD, please just leave the room. Seriously. There’s a playroom over that way.)

There was quite rightly a furore about Winston Churchill replacing Elizabeth Fry on the five-pound note, which would mean that female representation on the currency shot down to zilch. Until this recent announcement about Austen, we were facing a paper Old Boys Club of England – possibly less likely to chuck your antiques out the window while screaming ‘Bully! Bully! Bully!’ than members of the Bullingdon (here’s looking at you, Boris), but still inarguably destructive.

Why, then, are we belittling an author who has contributed to British society, simply because she does not encompass everything that we feel a woman should be? It feels like a tired repetition of what happens when the token woman appears on Have I Got News For You and ends up getting berated for not being the coolest, sharpest, funniest, best looking one there.

A female author’s impact on the world shouldn’t be lessened because their primary target today is women (I say ‘today’, because there’s evidence that Austen was not considered an author for women until relatively recently.) ‘Chick-lit’ as a term is just another way of deriding literature aimed at women, doing their rubbishy women things, trying to find love, eating chocolate and just sitting with their lady-friends talking about vaginas and stuff. By belittling Austen for being an easily readable author who still resonates with The Laydeez nowadays, while most of her female contemporaries are forgotten, except in academic circles, is basically insane. Ah, Austen, poor girly Austen: not a proper feminist who tried to be like men like Wollstonecraft. Not someone who fought men like Boudicca. Not someone who was swindled by men like Franklin. But a woman, in her own right, writing about women and their interactions with society. How dare she be all up in our faces, getting on our money, when she didn’t engage with more of the public sphere and male society in general?

This idea of Austen as inconsequential is reflected in the fact that historical male authors are not held up to the same stringent standards we hold their female equivalents up to. When Charles Dickens was put on the twenty-pound note, did anyone get their knickers in a twist over what he had contributed to England? Yes, you can argue that he influenced social reform in his time; that he wrote more novels than Austen; if you were so inclined, you could even try to argue that he was more of a ‘proper’ writer. But whoever defined ‘proper’ anyway? Austen’s novels are very well-written, acutely observed, and highlighted the real plights of middle-class women in her time. But she doesn’t engage with the supposedly important issues, because they’re women’s issues.

Finally, to those moaning that this mere novelist has knocked the great and mighty Charles Darwin off the ten-pound note, I leave you with this quote on novels from Austen’s own Northanger Abbey:

“It is only a novel… or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.”

Nope, it’s not evolutionary biology, but that’s the thing – being important isn’t linear. There are all kinds of important. My kind of important wears a bonnet and encouraged generations of people (including Elizabeth Fry’s replacement, Winston Churchill) to read. My kind of important’s encompassed in a the witty, brilliant and, some might say, inoffensive Jane Austen. And I, for one, am hella pleased that I can glance at her flattened paper face while I buy my fish and chips.

-SR

Couldn’t agree more. Complaining that Austen focuses on women’s issues is to undermine the value of those issues.

I think, to question Austen’s value as an author is to miss the point entirely. Austen supporters can argue for hours about her cutting prose and radical ideas, but these were clearly not the reason she was picked. She was chosen to be an inoffensive female representative.

The very fact the BoE chose *that* quote to decorate the notes demonstrates they do not understand Austen at all. “I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading!” is a comment made by Miss Bingley in order to attract the attention of Mr Darcy, who was too busy reading to pay any attention to her flapping. We are supposed to mock the character, not support her. The BoE did little more than run a search through Austen’s novels for the word ‘reading’ and declared that quote appropriate.

I doubt BoE see Austen as anything more than a charming lady in a bonnet who wrote silly books for silly women. Which makes her of her ascension onto the ten pound note very worrying.

It always perplexes me to see other feminists attempting to revise history so that women are placed on equal ‘level’ with men e.g. as leaders, intellectuals titans etc. This is not to downplay the importance of women’s history, and it is true that women did, sporadically, break through these boundaries, which offers some ‘empirical’ furnishings for our beliefs. But it is manifestly untrue to say that women contributed equally in this manner; we are better looking at women’s history as we do workers’, or minority ethnic groups’, that is, of an oppressed group. Only this will account for the (relative) paucity of women in ‘history’. If one becomes obsessed with writing them into traditional historiography not only does this affirm the legitimacy of our class society (that those on a pedestal should be revered), but it would seem to offer some affirmation of the notion that women could have broken through at any time, look, this women did, it’s the wider lot that don’t have the capability. No, the victory will come when you provide a rigorous socio-historical account of why women couldn’t attain these heights for the most part, and how this can be changed in the future, not by performing the conservative task of airbrushing the past. You make the point about the queen, which is indeed a silly one, but you reveal something when you say that it doesn’t matter because the monarch appears ‘regardless of gender’ – should the same not be true of who appears on the banknotes (assuming we need anyone to, or need banknotes, at all)? Or do you want a quota system that papers over the fact that we live in a society that doesn’t treat people the same ‘regardless of gender’? Why is this Austen thing such a big deal?

On the other point – Austen really is quite comfortable with patriarchal values in the last instance, just as Dickens was with capitalist values, even if he attempted to remedy its worst excesses. It is tokenism, again, by this measure. It is woman as image, and not as source of strength equal to all other beings; and while this may provide some relief whilst buying your fish and chips, doesn’t really concern the serious matters at hand.

Are her novels authentically ‘British’? Possibly, they provided a romantic view of, while signalling the impossibility of a return to, aristocratic and gentry life during the early industrial revolution, but then most countries have to suffer such nonsense during their transition. She’s a good writer on human relationships. This isn’t of concern, again.

Well, you can’t win, then. I agree that it is intellectually dishonest to pretend that women’s contribution to “history” as it is conventionally understood, is the equal of men’s, and it is not equivalent because they were in effect prevented from operating in the public sphere and had to be exceptional, privileged or lucky to make their mark even in a circumscribed field. But if you accept that it might be reasonable to acknowledge the existence/meagre (in conventional terms) achievements of one half of the population by an image on the banknote, and you argue that by singling out for representation one who despite the odds breaks the barriers is somehow legitimising those barriers, or alternatively that anyone who did so must have had to collude with the patriarchy without attempting to destroy it, then you will end up with some symbolic faceless representative of the noble oppressed female masses. What would that achieve? I don’t think that anyone would think that featuring individual men of achievement from humble backgrounds (e.g. Newton, Faraday) denies the existence of a class system or grinding poverty of most men at the time, or implies that they endorsed it. Images of historical women’s achievement are significant, even if that achievement was constrained by the conventions of the time and did not involve an analysis of, or solution to, female oppression, even if it effectively described it. I also agree that there are other women one might choose who are less anodyne in social/historical terms (even looking at the canon of female novelists one could propose George Eliot) and that she was seen as a safe choice. But I think you are in danger of throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Austen is the perfect author to appear on banknotes for her incisive views on money and society, especially when considering women’s role in the marital marketplace. That opening line of Pride and Prejudice, says it all, ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife’. All served up with a dash of irony. Yes, she was only interested in the middle-classes, and politically, she was no radical (see Sense and Sensibility)ebut to describe her novels as ‘light’, ‘easy’, ‘not engaged with the public sphere’(Fanny Price’s oblique remark on slavery in Mansfield Park, anyone?) or chicklit (See Northanger Abbey for her views on mass-marketed novels for women) is not to read them at all. Perhaps we could actually bring her impressive body of work into the debate too?

Surely the incredibly famous opening line to P&P is one of the most self-aware and brilliantly put sentences Austen constructed? She was a master of saying the things women weren’t supposed to even think and writing under her own name.

She’s amazing. As is her amazingly astute and brave writing, which is still to this day being sold to millions in many different forms.

This comment has been removed by the author.

I’m entirely happy to see Austen on the £10 note. I like Austen and often frustrated at the often repeated idea that because she was funny she wasn’t serious. It is possible, and often quite useful, to be both.

There are a couple of tiny errors in this article. None of them really detract from the argument made, but they do distract the pedantic, of which (horribly) I am one:

“Well, all of those women should have a shot at being on our money, and it’s unfair that the Bank of England maintains their tokenism in having one woman on its notes and three men.”

The Bank of England’s ratio is worse than that, it’s one woman to four men. The £50 note features both James Watt and Matthew Boulton on its reverse.

“Until this recent announcement about Austen, we were facing a paper Old Boys Club of England”

We might have been facing an Old Boys Club, but it was not an exclusively English one: Adam Smith and James Watt were both Scottish. (There aren’t Welsh people in this club, a problem that the Welsh can’t correct by forming their own club as they don’t have any banks with the right to issue banknotes; Ireland’s only member, the Duke of Wellington (£5), was removed by bouncers in 1991. As the UK’s central bank, if the BoE must go around celebrating people, it’d be nice if it represented across the UK (or at least Wales) and across ethnicities and sexes.)

While I’m talking, vaguely, of Scottish people. The Clydesdale Bank’s £50 note not only features a woman, but a suffragist: Elsie Inglis. I’m not as well versed in her accomplishments as I’d like, and wikipedia doesn’t go into much detail, so if you’d like to read about her, a reasonable place to start is here: http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/Winglis.htm

(I’m a little drunk and the first time I posted beneath this article I came across as a bit crotchety. I deleted that because I didn’t really mean to be; I hope this is an improvement.)

Thanks for those clarifications – I didn’t consider the new £50 note when I wrote this, and in regard to the England comment, and you are of course right about Adam Smith and James Watt, India.

In response to your point, Catherine, the point I was making was that people who deride Austen often deride her as light and easy. My point about her not engaging with the public sphere relates to the emergence of the private and public sphere in the eighteenth century, and how she engaged with the domestic, only ever alluding to larger issues, for example, war. I agree that her body of work is incredible impressive and my point is that it is being derided constantly for being likeable.

I think that to use the idea that Austen is popular to attack her as a choice is pointless – The Bank of England was not going to pick a controversial figure for any of its banknotes, regardless of sex. Their previous choices highlight this.

Finally, in regard to ‘rewriting history,’ it’s simply a sad fact that women are under-represented in history because of a society in which they were not encouraged to participate publicly, and we have to look harder for their contributions. This does not make their contributions less valid, just less recorded.

Hi Sairah,

I was actually in agreement with you & recognised that you were deriding those who see her work as easy. I’ve been really peeved as a lot of media comment which seems to be based on the TV & film adaptations rather than her work, or those who critique Austen personally. Which is stupid on two levels: I don’t remember anyone criticising BoE’s decision to feature Dickens as he was horrible to his wife, and Austen’s personal letters reveal a women with a raunchy sense of humour anyway – far from the prim quiet soul painted by ‘commentators’. Hence my vexed post which was more me letting off steam in general. That’s an interesting point about the emergence of public/private spheres (though working-class women didn’t disappear into the domestic space!). Your point also highlights sexism inherent in a lot of examination of literature: why shouldn’t the domestic be as ‘important’ as the public?

All the best

Cath

Oh, sorry, I misunderstood!

I agree with your points – there are so many assumptions about Austen, a lot of them wrong. I think there is a general sexism towards women in history in general, and studying female authors has certainly proved that. It all relates back to women being ‘in their place.’ The renewed interest in Austen because of the new note I think is to do with this idea, but this time through placing Austen as a writer of women’s stories, rather than proper literature, which of course is nonsense.

It’s really great to hear everyone’s views though – especially as I have found so many in agreement with, or at least able to appreciate what I am saying. Thanks very much for your feedback.

Does anyone else not think that labeling Austen’s presence on the £10 note as “female representation” totally summaries the purpose for her selection? I believe that, gender regardless, if someone is worthy of having their face on money, their face should be on. I think any feminists seeing this as some kind of victory should note it’s hollow qualities.

She was picked because she was a woman.

Yes, she was a woman who wrote great books, but there are men (and women) out there who, I believe, are far more worthy that Austen. Austen is a fashionable, crowd-pleasing option.

I just want to mention, that, although she’s not terribly revolutionary now, as much as I love her, she WAS a pretty big deal on the women’s scene back then, when she was writing. The women in her books didn’t faint all the time! They spoke! They were the main characters! There were an equal amount of men and women in her books!

Also – it’s not like she COULD engage even more with society than she already had, she was a woman in the late 18th century. I’m surprised she was able to comment so much on society in her books what with the ‘women only occupy the home’ argument that was going on back then!

Also, she’s a good writer, at least in my opinion.

Oh, also – she didn’t write enough books, or as many as Dickens? GUYS, SHE DIED AT 41. Not much you can do about that! She had books in the works while she was ill, actually.

I’m happy about this!

- Laura

“not-really-revolutionary author”

it’s clear you never read her, and know nothing about her and the period she lived in.