Darcy is dead, so Bridget is back! Having disappeared into blissful obscurity for 14 years, the woman who gave us singletons, smug marrieds and emotional fuckwittery, and in so doing spawned an entire genre of fiction, has returned to our bookshelves – or, rather, to our Kindles, the world having moved on a bit since Bridget first rhapsodised about the wonders of 1471. Despite the lamentations of fans, it was inevitable that the too-perfect-by-half Darcy would have to be killed off – after all, the pursuit of happiness is the raison d’etre of chick lit and, mostly, that means bagging a man.

For some feminists, this rankles like biscuit crumbs in bed. Add Bridget and her successors’ obsession with their weight, as well as their cupcake- and cosmopolitan-fuelled experience of female friendship, and belief that there are no problems that can’t be solved by a hot date, a warm bath or a cool handbag, and we could end up shunning the entire genre. But I think we should give chick lit another chance. And I even put 85,000 words where my mouth is and wrote a chick-lit novel of my own.

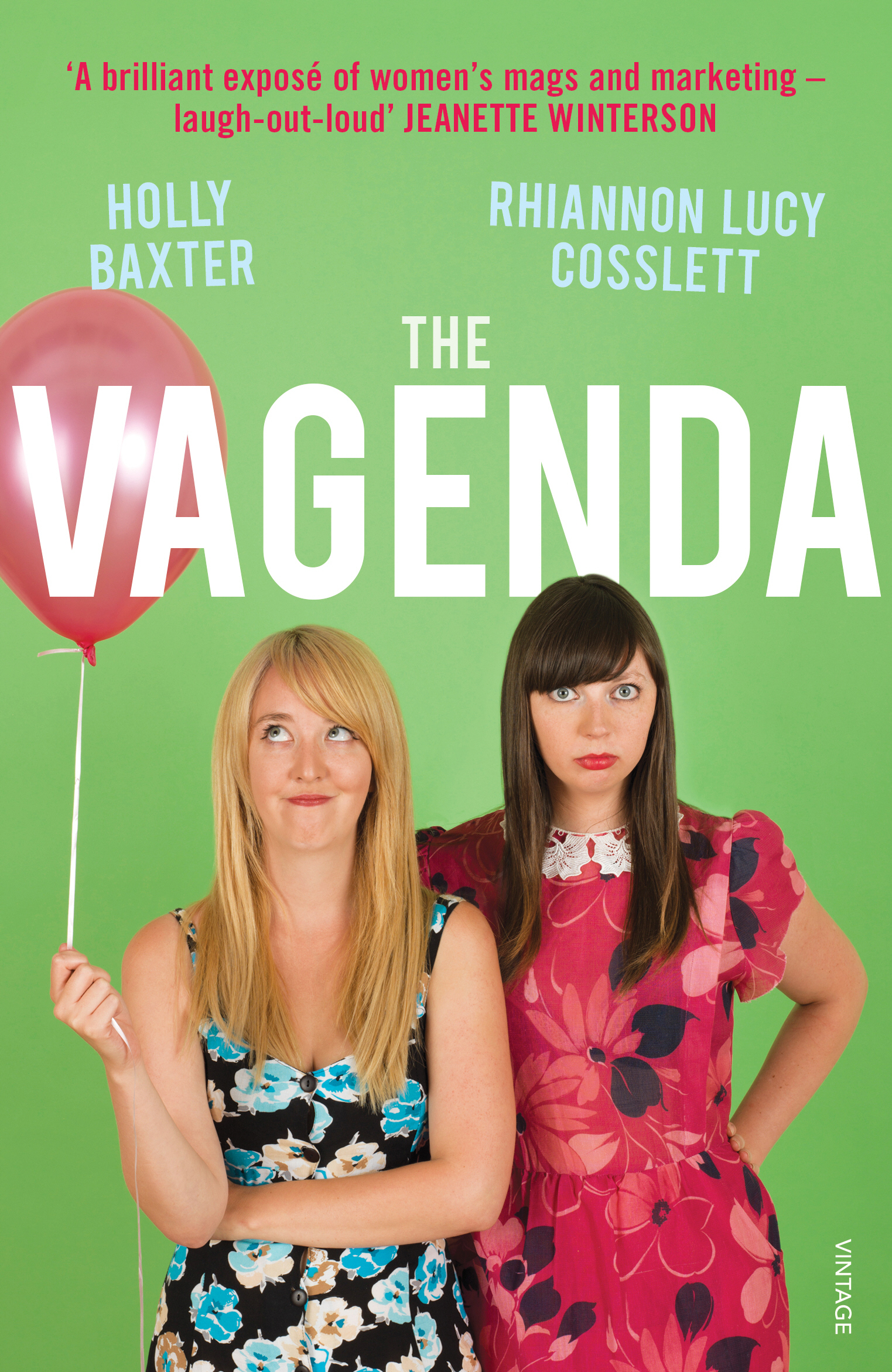

Leaving aside the obvious fact that that we’re allowed to read what the hell we like – even if it’s all about shoes and chocolate and Mr Right – even, in fact if it’s profoundly misogynist - let’s look for a second at the label “chick lit”. To state the obvious, it pigeonholes writing for and about women into a category that’s less important, less serious, less good. This is not on.

Of course, there are many, many books in the genre that do our cause no favours at all. Katie Price’s notorious Angel series sees a woman finding true love in the arms of a footballer, via the route of glamour modelling – so far, so stereotypical. In that yawningly similar vein, Alison Kervin’s WAG series has a cast of women so vain and vacuous you wonder whether the author is actually the editor of Nuts magazine having a laugh in his spare time. And if that’s not enough for you, the toe-curlingly named genre “yummy-mummy lit”is full of unsympathetic tiger mothers as shallow as they’re sharp-elbowed.There’s not much fodder for the real-life woman amongst any of them.

So that’s the bad and the ugly. But there’s also a surprising amount of good out there, despite what a small band of media snobs might tell you. Many writers of commercial women’s fiction self-identify as feminists: Rosie Fiore, Meg Cabot and Marian Keyes (whose books embrace such trivial, ‘girly’ issues as addiction, bereavement, rape and domestic violence) are just three.

One of the classics of the genre, Sophie Kinsella’s Shopaholic series, portrays a heroine in the grip of a consumerist frenzy – but readers are just as likely to be left questioning the values of a society so obsessed with Stuff as they are hankering after another pair of Manolos. The assumption that because it’s ‘chick lit’, it must therefore have no subtext is woefully patronising. Equally, Milly Johnson’s An Autumn Crushmight depict romance and motherhood as the epitome of womanly achievement, but it also places a high value on female friendship and scores extra points for being fat-positive. In The Devil Wears Prada, the heroine’s boyfriend barely features, so sidelined is he by the demands of her career. Jane Fallon’s Getting Rid of Matthewhas the heroine’s married lover finally leaving his wife for her, only for her to realise she doesn’t want him any more.

One of the classics of the genre, Sophie Kinsella’s Shopaholic series, portrays a heroine in the grip of a consumerist frenzy – but readers are just as likely to be left questioning the values of a society so obsessed with Stuff as they are hankering after another pair of Manolos. The assumption that because it’s ‘chick lit’, it must therefore have no subtext is woefully patronising. Equally, Milly Johnson’s An Autumn Crushmight depict romance and motherhood as the epitome of womanly achievement, but it also places a high value on female friendship and scores extra points for being fat-positive. In The Devil Wears Prada, the heroine’s boyfriend barely features, so sidelined is he by the demands of her career. Jane Fallon’s Getting Rid of Matthewhas the heroine’s married lover finally leaving his wife for her, only for her to realise she doesn’t want him any more.

In my ‘chick lit’ novel, It Would Be Wrong to Steal My Sister’s Boyfriend (Wouldn’t It?), I consciously set out to create a heroine who self-identifies as a feminist. I gave my characters real problems. I tried to make gay people just part of the cast, not mincing caricatures. I wanted to depict attachment parenting as a normal way to care for a baby. I made Ellie and her friends properly sweary, which is how my friends and I talk – and to my surprise I’ve only had one piece of negative feedback about that. But the book is still chick lit – although she’s a strong woman with strong views, Ellie’s not immune to having her head turned by a pair of shoes or her principles swept aside by lust. She longs for a happy ending – and, as a feminist, I’m okay with that.

- SR

- SR

I’m so happy to have read this post – the other day I bought a chick-lit book called Never Mind the Botox – Rachel and have been feeling guilty about it ever since (being somewhat of a literary snob I also had the above mentioned stereotyped views I’m afraid). I was drawn to the book nonetheless and also had a suspicion there was nothing wrong with that – and now I know that for a fact.

Balanced. Interesting. Never thought about it like that! Bravo

Just bought your book, I hope you get my 6 australian dollars!